Lisa Raitt on taking care of her husband as he struggles with young-onset Alzheimer’s

In the early hours of the morning, Bruce Wood will wake up next to his wife, former Conservative MP Lisa Raitt, and start muttering.

When your spouse is also your caregiver…

“I’ll say to myself: ‘Please go back to sleep.’ But if he doesn’t, he’ll start jabbering to himself, and it’ll get louder and louder and louder,” said Raitt, who held several cabinet positions under Stephen Harper.

“Then he’ll jump out of bed, and then he’ll start fighting with the bed sheets or fighting with a phantom person in the room,” she told The Current host Matt Galloway.

In 2016, at the age of 56, Wood was diagnosed with young-onset Alzheimer’s. Earlier this month, Raitt shared a short video of his distress on Twitter.

She said she’s sharing her experience publicly to let other caregivers know it’s OK “to tell the really bad stories.”

“You suffer in this, silent and alone,” she said. “What I wanted to do is bring it out of the shadow.”

“He was becoming so agitated, I thought I had to distance myself,” said the former MP, who represented the ridings of Halton, Ont., from 2008 to 2011 and Milton, Ont. between 2011 and 2019.

“And I came down to sleep on the couch, and he found me and he just punched me in the head.”

Wood’s doctors have since adjusted his medication to keep him calm, she said.

“The reality is he’s six-foot-two, he’s 250 pounds, and he can kill somebody,” Raitt said.

“It’s awful because he’s a good man. So, you tell yourself it’s the disease.”

According to the Alzheimer Society of Canada, roughly 16,000 people in Canada have young-onset dementia — an estimated eight per cent of all dementia diagnoses nationwide. A case is considered young-onset if diagnosed before the age of 65, though it affects some people as young as in their 30s.

Subtle symptoms, years before diagnosis

Raitt remembers changes in Wood’s mood and personality dating back to 2011, three years into their relationship. By the next year, he was having trouble reading documents at work, or with tasks, such as ordering in restaurants.

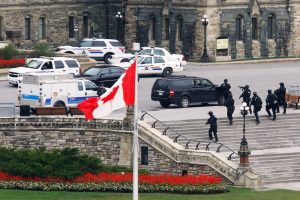

During the 2014 Parliament Hill shooting, Wood didn’t call to check on her.

“It didn’t even occur to him that I was in any kind of danger,” she said.

At the time, Raitt thought it was a sign that Wood didn’t care about her and their relationship was breaking down. But his diagnosis came 18 months later.

“Turns out that’s a story you hear an awful lot … that people get divorced, people lose their jobs with young onset before they’re diagnosed,” she said.

“And then everyone goes: ‘Oh, that’s what it was.'”

Patients and doctors may not recognize symptoms when they appear because of the disease’s rarity in young people, said Jessica Bertuzzi, a spokesperson with the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

Young-onset Alzheimer’s can progress much faster than in people with dementia later in life and has different “personal, social and economic consequences.”

They might still be working and have a mortgage and bills to pay or have younger children, who themselves need care and financial support, she said.

A younger diagnosis also means that many with early-onset dementia are looked after by family members.

“The burden of care is very great for them because there’s so many other responsibilities at that time [of their lives],” said Bertuzzi, who is the public relations and education manager for the Sudbury-Manitoulin North Bay branch.

‘I’m hitting my limit’

Raitt, who is now vice-chair of global investment banking at CIBC, said she is lucky to have help from professional caregivers for part of the day. But Wood requires constant attention and is unable to shower, dress and is “getting to the point where he can’t feed himself.”

“From 4 a.m. until 10 p.m., he’s an out-of-control toddler with a lot of strength, and the temper tantrums to go with it and the inability to sit down or sleep.”

But the cruelty of the disease means that every few days, you might “get 15 minutes of the clarity of what you once had in a relationship with your husband,” Raitt said.

She explained that might be “having your partner know who you are and watching television and smiling at a joke or saying, ‘I’m really tired.'”

“You almost think to yourself, I can deal with the 23 hours of real crappy time to get this one snippet,” she said.

“But the reality is your body can’t. I thought I could just barrel through anything in life, and I’m hitting my limit.”

Raitt has found support in group therapy and online discussion forums, where other caregivers share their experiences, which Bertuzzi says is really important.

“Unless you’re living in this journey, it’s really hard to understand some of the challenges that can occur,” said Bertuzzi.

Living with an ‘ambiguous grief’

In the years following Wood’s diagnosis, the couple travelled as much as they could.

They also got married in Raitt’s native Cape Breton, N.S., less than two months after his diagnosis.

Both had been married before and never intended to marry again, but Raitt thinks it has given Wood a sense of security.

“He wears a wedding ring. He looks at it. He knows he belongs to someone,” she said.

“He may not know he belongs to me because that part is a little bit fuzzy now, but he belongs to someone.”

Bertuzzi said caring for someone with young-onset Alzheimer’s comes with an “ambiguous grief, where you’re grieving the person that is still physically there.”

“There’s hard things to accept, and it’s hard to watch your loved one change over time,” she said.

Raitt said those changes can come in a way that “creeps up on you.”

“He calls me Mommy,” she told Galloway, attributing it to her cleaning and dressing him.

She said she stopped correcting Wood at the end of the summer.

“You wake up one day and you realize: I’m not a wife anymore.”

Long waits for long-term care

Raitt is looking into long-term care facilities, but said wait times have gotten even longer in some locations due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I need a place where Bruce can go to be comfortable, to do activities that are appropriate to his age and his physical ability,” she said.

“Everyone wants to have a dignified life.”

In the meantime, she worries about getting his symptoms under control, and preventing further violence.

Raitt has cameras in their home — originally installed to check on Wood while she was away at work — but now to record any incidents.

Bertuzzi said that each diagnosis is different and while some people may never exhibit violence, some do in what’s called a “response behaviour,” often out of frustration and an inability to communicate effectively.

“Imagine you had an awful, awful headache and you couldn’t tell your loved one your head was hurting to access Tylenol or Advil,” she said.

“That frustration builds up.”

‘Put your own mask on first’

Bertuzzi warned that when wait times for care facilities are long, care partners need community support in order to protect their own mental and physical health, and guard against depression or physical impacts like exhaustion.

“It’s really important that care partners feel as though they have the support to lean on to assist them on this journey, because we can’t ask anyone to do this on their own,” she said.

The Alzheimer Society offers education sessions and support groups, tailored to people living with the disease and those who care for them. During the pandemic, they’ve adapted their in-person groups to virtual sessions.

For anyone caring for a loved one with young-onset Alzheimer’s, Raitt encourages them to care for themselves as well.

“You hear the old adage, you’ve got to put your own mask on first before you put the mask on the person next to you,” she said.

“I think talking about it allows other people to have that recognition moment. And if it’s only one family out there that I help, I’m actually good with that, because it matters.”

Redes Sociais - Comentários